A Cross Cultural Examination and Manic Outpouring of One of Pokémon’s Most Popular Creations

Dragons have been found all over the world. From the rage-filled gold hoarding dragons of Western Mythology, to the Rain Gods of Power and Wisdom of the East - dragons have been a part of myth and legend since what seems like the era of mankind. The etymological word for Dragon comes from the Greek word, “drakōn” which means “large serpent”. And while Pokémon has explored, broadened, and stretched the term to many a Pocket Monster, perhaps no other depiction has been so culturally diverse and showcased as the original and first “Serpent” Dragon as Number 130 - The Atrocious Pokémon.

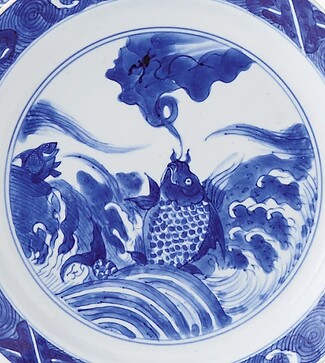

The Chinese myth of Longmen or “The Dragon Gate” is so well known that most folks don’t even know the name but know the story - based on real life occurences, many Carp swim a river upstream - up and over a waterfall, leaping in an attempt to cross. It is said that, on a legendary Mountain, once a Carp succeeds in jumping over the top of the waterfall, it will cross the Dragon Gate and become a Dragon. The myth is cross-cultural, having variations through Eastern countries including China, Japan, and Korea. The story is said to originate along the Yellow River by the boarder of Shanxi province and into the Longmen Mountains or “Longmen Shan”.

This myth would go on to be the official inspiration for the first Dragon Pokémon - Gyarados alongside its pre-evolved form, Magikarp. As canon in the legend, Magikarp must “Struggle” and endure hardship in order to properly evolve into a Gyarados - symbolizing the origins of its myth. Gyarados itself may be inspired by the Green or Blue Dragon of the East - The Azure Dragon “Qinglong” which also has ties to Japan as one of the four Guardian Spirits as well as Korea along Goguryeo tombs. Each of these depictions associates the Azure Dragon with Water and Sky - a fitting type for the Water/Flying Pokémon known for its Dragon moveset.

The First Pokemon Snap game even has you spur a Magikarp to leap over a literal mountain - only by accomplishing such a task do you get the chance to meet Gyarados later at the top.

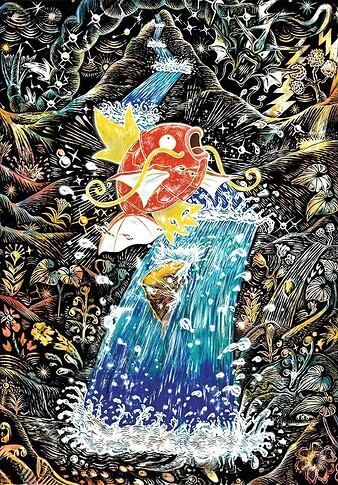

In the TCG, Magikarp’s “useless” Splash becomes evident of its special hidden talent to overcome struggle by showcasing its leaping ability in several different cards. Gyarados itself showcases in tandem, seemingly at the top of mountains. But no other card so well depicts the Longmen mythos as Shinji Kanda’s 2023 depiction. Kanda, known for his ethereal works and master of monsters, gods, and legends outside of Pokémon, was the first and so far only to showcase the entire origin myth of the Dragon Gate symbolism in the TCG. In 2023’s Triplet Beat, we see Magikarp, making its way up a waterfall, and atop that long mountain, above the waterfall, an almost spirit-looking Gyarados. The goal of becoming an Expert Splasher.

But the aspects of the Dragon symbolization don’t stop there when it comes to Gyarados. While other Pokémon may show up in different clothes, holding certain objects, etc from different cultures - most noticeably Pikachu - Gyarados not only shows up in cultural contexts but BECOMES part of the myths and legends related to that land. Through the use of both the TCG and the non-TCG, Gyarados predominately shows up as mountains, fountains, flags, and statues in the context of different regions. And while most of them show up in the context of Japan, we’ll see how this rage-induced Dragon appears in different cultures - with the most notable and interesting depiction pre-dating the Longmen mythos itself. And how said depiction would go on to inspire an entirely different Pokémon altogether.

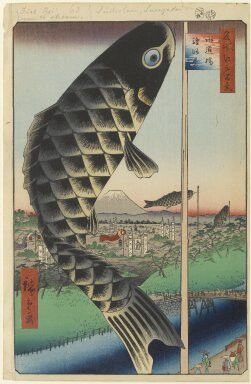

Every year on May 5th, Japan holds it’s Kodomo no Hi (子供の日) or “Children’s Day” Festival. Carp Streamers, called Koinobori ( 鯉のぼり) decorate the landscape to symbolize the success of children - the carp being symbolic of future success by their ability to swim up waterfalls. Originally it was in celebration to the future success of young boys of a household during the Edo period (the event being previously established as “The Boy’s Festival”) but has since been inclusive to all children on “Children’s Day”.

The celebration starts near the end of April but peaks on May 5th - the official date for Children’s Day. The streamers themselves have some basic parts but there is always some deviation:

Yaguruma - think of this as a spinning wind vane or wind wheel at the top of the pole.

Fukinagashi - the flying dragon streamer - which is the highest streamer.

Koinobori - the carp streamers themselves - usually on the lower ends.

Colors and placement usually have symbolic significance as well since the top one is black and typically depicts the father, red the second as the eldest son, and blue the third as the youngest son. But this has since been outdated as the red one can also now also represent the mother, and all children are celebrated with the use of varying colors - least to say, modern celebrations depict multiple colors and placement variety.

In truth, a plethora of materials and imagery of this has poured out featuring both Magikarp and Gyarados even into the 2023 year. In Pokémon Season 1 Episode 53 “The Purr-fect Hero” [in Japanese: “It’s Children’s Day! Everyone Come Together!”] a Gyarados Koi Flag is spotted alongside Goldeen and a Magikarp below. This same scene would find itself in the Carddass Anime Collection. Though Magikarp gets the majority of love with official Koi Streamers, a duo pair of Gyarados and Magikarp official streamers were produced in the 2000’s while a Daichiipan package featured both red and blue Gyarados. Though there are countless depictions of Magikarp and Gyarados as Koi Flags, my favorite above all else has to go to the 1997 Pokemon Calendar May Insert illustrated by ever-talented Kagemaru Himeno.

During the festival, Gyarados and Magikarp have made real-life appearances as streamers. Funny enough, the tradition of Koinobori originates from the very same Longmen mythos that Magikarp/Gyarados come from - as a representation of this transformation from childhood (Magikarp) to adulthood (Gyarados). And, as we we’ll see, they even have a counterpart commemoration in celebration of adulthood as well.

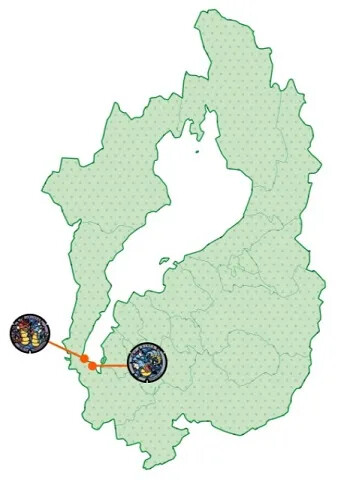

Released August 2nd, 2000, a card showcasing Gyarados swimming through a body of water was awarded to participants of the Japanese World Challenge Summer Tournaments. It was handed out during July and August of the same year at the Hiroshima Sun Plaza located in Chugoku and was known as the Lucky Stadium - Chugoku/Shikoku Print.

This card may be a nod towards Shikoku in particular as there is a famous dragon-shaped river known as the “Yoshino River” of Kochi Prefecture. This river flows from Mt. Kamegamori to Lake Sameura, which forms the dragon’s head (see above picture). Though while there are many bodies of water in Japan associated with Dragons, the head of the river was established in 1975 due to the completion of the Sameura Dam.

The Hiroshima Sun Plaza is known for its annual “Seijin Shiki” or “Coming of Age” ceremonies, one of few Prefecture-based locations, where young adults are recognized from their leave of childhood on the Second Monday of January. This is a foil to Japan’s “Children’s Day”, which celebrates children - and so with the latter being associated to Magikarp, Seijin Shiki or Seijin no Hi may be a nod to when they become Gyarados. And as the connections to dragon continues - we see yet another connection in the year 2000 itself.

The Year of the Dragon.

In Chinese mythology, the Dragon is known as “loong” or “lung” and makes up the 5th animal in the 12-year cycle in the Chinese Zodiac. Each animal has associations with personality traits as well as what to expect for the year. With the Year of the Dragon - it is said that “Dragons are hovering in the sky to give rain.” In the legend of the “Great Race”, it is said the order of the animals are the order in which they became known to the Jade Emperor by racing to cross the river. Though it was thought that Dragon would come first, in the story the Dragon explains how it had to give rain to people in a neighboring village and then, when seeing the 4th animal, the Rabbit, struggling to cross, gave it a puff of air to make it the rest of the way on a log. Because of this, the Dragon is associated with power, wisdom, and good nature though the negative traits being associated with stubborness, anger, and arrogance.

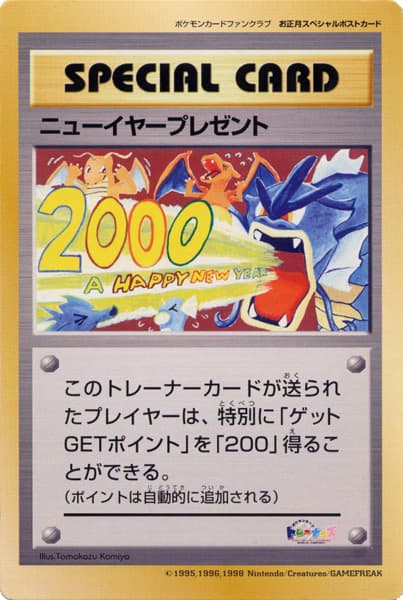

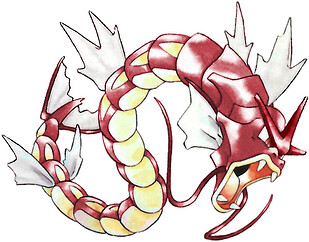

The Year 2000 was a special year for Gyarados. It was the year that Generation 2 debuted in English and, with it, Gyarados became the first ever Shining/Shiny Pokemon. But with this year came a plethora of Gyarados related goods to celebrate the year of the Dragon. One of the more original highlights - A Pokémon Getto Da Ze! 2000 New Year Postcard was released with the 1st Grade Elementary School Magazine 2000 January Issue featuring a Dragonite (a popular feature with the Pokémon) and Dragonair alongside Gyarados to make the Year 2000.

But no other depiction may be as famous as the one created by Tomokazu Komiya in the New Year Present Postcard Jumbo. Released in the year 2000 for Pokemon Fan Club members, Komiya’s depiction showcases Gyarados using it’s signature move - Hyper Beam - to blast all other Dragon Pokémon away - celebrating the New Millennium.

But the Chinese Dragon connections do not end here. For they would find themselves connected to a very famous campaign. And with it, a hidden symbol of a serpent biting its own tail.

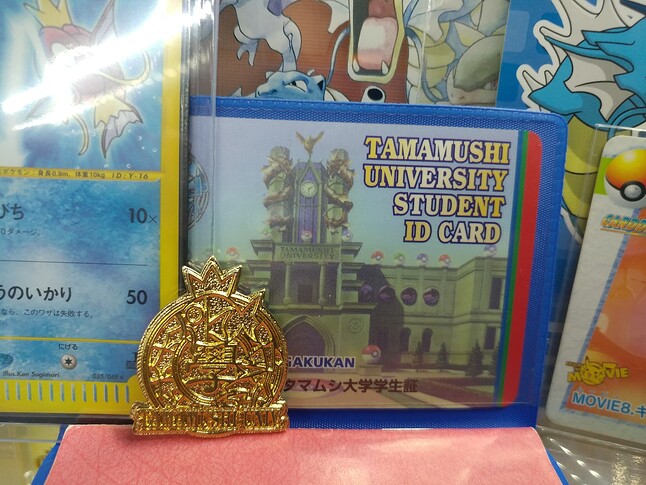

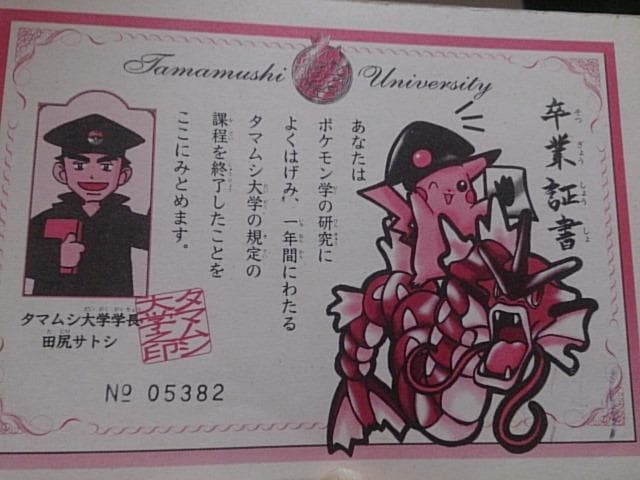

In 1998, Pokemon began one of its most ambitious campaigns in Japan. Taking thousands of “students” by storm, they began the Shogakukan Tamamushi University Campaign which required the completion of an entrance exam published in a May 1998th issue of “Elementary School 1st Grade”. Completion of the mailed in exam brought them closer to a Hyper Professor Test and upon completion of that, the top 1,000 students would receive the legendary Tamamushi “Unikarp” Magikarp as a recognized Pokemon Professor. Alongside this campaign, accepted students received multiple materials including a gold pin of the logo, a red booklet, a blue holder, a certificate, two pencils, and this same Student ID card.

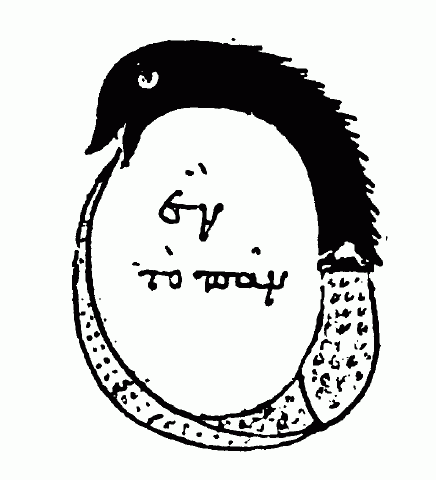

Magikarp has become a common Pokemon symbol for learning and growth due to Japan’s phrase of “Koi no taki-nobori” [鯉の滝登り] or “Carp ascending a waterfall” - a direct tie to the Dragon Gate myth. But looking further we see an even older symbol:

With Magikarp noticeably at the top, we see Gyarados is biting its own tail almost like the rebirth symbol of the ouroboros - with the Kanji “学”, meaning “to learn” embedded in the center. The Ouroboros being an ancient symbol, it first appeared in primarily Western locations - later being adopted as a symbol for Alchemy. In Egyptian Mythology, it has associations with the Egyptian Snake God, Mehen or “coiled one” which depicts the beginning and ending of time and was also symbol of constant growth and renewal. In both Greek and Norse myth, it is associated with the “one-ness” of the world. Perhaps the Dragon Gate Myth and Ouroboros ties well into this symbolism then - as to take the road of learning is a continuous and unending process.

To become a Professor then, one has to advance the waterfall of learning so that one may become a Gyarados. We see this reflected in the pillars of the Tamamushi University itself with two Gyarados statues climbing the pillars to attest the advancement of their Poké-education. This dragon symbolism is also manifested in the legendary Unikarp itself, with a Magikarp capable of learning “Dragon Rage” - a move typically resigned to its evolved form.

As is the case with Carps climbing the Waterfall of Education and becoming Dragons, it seems too that another test was in order after folks would win their Unikarp. For in March 1999, another exam was offered as a “Graduate” exam. Though not as involved as the previous exams, winners would be provided with one of a few different certificates. One of which showcased a Pikachu riding a Gyarados - printed with red ink - perhaps the first ever depiction of a Red Gyarados until Gen 2.

The Dragon Gate Myth and associated legends have made their impact and continue to do so with Magikarp and Gyarados. Yet one would be mistaken to think that that is all they are associated with. As we will see, there is much still to explore in Japan, and even further than its borders.

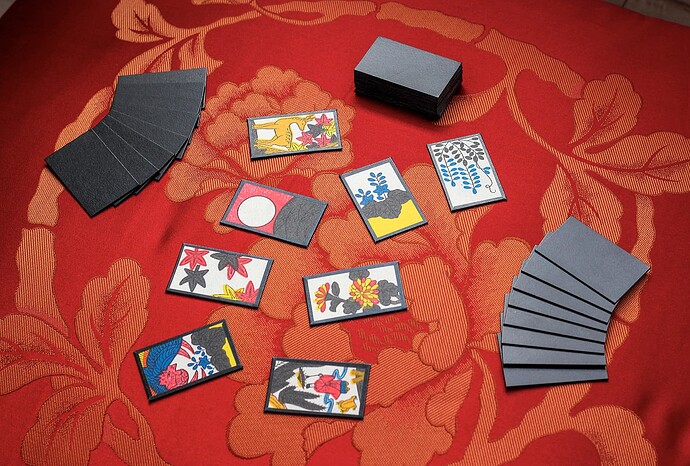

In 2014 Gyarados was featured alongside one of it’s most notable duos - Dragonite - as a Hanafuda Card. Featuring Pine Trees for the “January” suit, this card was one of several Pokemon cards from the original 151 featured in Pokemon’s first ever Hanafuda set.

A popular card game during the 16th-17th century during the prohibition era in Japan, each suit of these “Flower Cards” was based on the different months and held different points depending on the imagery. With this card in particular encasing a poetry paper strip or “tanzaku”, this card would have been automatically worth 5 points.

In regards to the imagery - pine trees native to Japan are known as “Matsu” which retain their beauty while seemingly unaffected even in Japan’s harshest winter month - January. These trees also hold an interesting association to Dragons due to their long lived nature and their elongated and flowing branches - a popular tree for the practice of Bonsai. One such association is the Legend of the Dragon Lantern Pine or “Ryuutoo no Matsu” in which it is said that lost fishermen were guided through a dark storm on the sea by the lights of a Dragon God via a Pine Tree on the shore.

Although it is uncommon to see Gyarados connected with so many life-saving legends, there is still at least one more Japanese myth to explore.

Built in the early 1600’s during the Edo Period and reconstructed later after the bombings in World War II, Nagoya Castle is one of the most famous castle towns in Japan. The golden statues that sit atop it are golden Shachi - said to be “tiger-headed dolphins or carp” that summoned rain and were seen as protectors from fire.

Like many Japanese Dragon myths, Shachi may have also stemmed from the Chinese “Chiwen” - both are said to be born from the sea, carrying great amounts of water inside their bellies during their flight. Both are protectors of fire and are often used as talismans on roofing and other types of building or fencing. They are associated not only with oceans but lakes and rivers - though it should be noted that unlike Shachi, Chiwen are also said to protect from floods and typhoons.

And in 2016, as part of a Pokémon Travel Campaign, a Nagoya Castle Pokémon Pin from Pokemon Center Nagoya featured Gyarados as one of two Shachi atop Nagoya castle, with a regular Shachi on the opposite end of the roof.

It’s interesting that Gyarados is featured alongside a Shachi as the former is known for destroying cities rather than protecting them. Perhaps it is due to their tied water nature they’re depicted together. Or perhaps it is to represent the dual nature of preservation and destruction. Perhaps it’s both! In either case, when reading the history of these tiger headed beasts, it’s hard to believe that Gyarados has yet to appear as anything other than a rain or protective deity. But as we’ll see, that isn’t always necessarily the case.

On April 17th, 2019, Pokémon Center Singapore held its Grand Opening showcasing their new mascots: Lapras and Celebi (alongside Pikachu) - with Gyarados becoming a pseudo-mascot. During the opening, flyers, postcards, and EZ-Link cards - a type of transit pass - were available to folks for a limited time - featuring the Grand Opening Image by Kouki Saitou pictured below:

The design for the Grand Opening items included several nods to Singapore’s cultural landmarks and special meaning for its Main Mascots - Lapras & Celebi. Lapras was chosen due to Singapore’s cultural roots as a major seaport where trade was taken in by boat. Celebi was chosen due to its focus on Greenery - especially in concerns to the “Garden City” - housing the largest glass greenhouse in the world. The image would go on to hold other symbolic representations if one were to look closely enough.

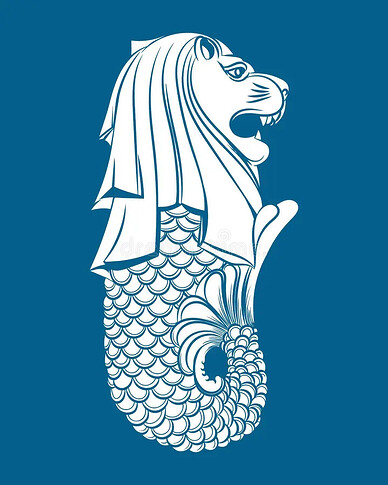

Gyarados in particular received special attention as well. The Pokemon is featured as the famous Merlion Statue from Merlion Park. The Merlion being Singapore’s official mascot with its Lion’s Head representing Singapore’s original name, “Singapura” meaning “lion city”, and its fish body representing its roots as a fishing village once called Temasek.

Though the symbolism of the design was created in the 1960s, the Merlion bares a strikingly similar resemblance to the Shachi and Chiwen of Japan and China. Whether this was inspired by or simply a coincidence can easily be argued due to the naming scheme of Singapura & Temasek. And though the connections to water and dragons continue to be existent, there’s at least one exception that possibly represents the inner fire and rage that Gyarados is known for.

Waikoloa Village, Hawaii - the 7th World Championship featured artwork in honor of Hawaii’s rich culture, tradition, and mythology. With tropical Pokémon featured in the traditional dance form of Hula - a dance that holds deep meaning to storytelling, we even see Gyarados encased in stone like a fountain upon Hawaii’s most famous volcano - Kilauea.

Kilauea is one of the world’s most active volcanoes with the most recent eruption earlier this month on September 10th, 2023. In old tribal chants, it is said to have a “fickle nature”, mirroring Gyarados’ natural temperament. It is also associated with Pele - the goddess of fire and volcanoes. Referred respectfully as “Tutu Pele”, she is also known by the epithet of “Ka wahine 'ai honua” or “The earth-eating woman”. Having multiple legends attached to her name, one such story, Kai a Kahinalii (Sea of Kahinalii), describes how she was born near the sky and, from her head, produced the sea that would eventually flood the earth and bring water to Hawaii.

Despite the associations towards rage, fire, and water, it is possible that Gyarados’ depiction was chosen due to Hawaii’s “Mo’o” legends - deified ancestors (or " 'aumakua ") that take the form of reptiles which are said to have power over water and the weather. For when a Mo’o passes away, its petrified body becomes a part of the landscape itself.

Due to the focus on Gen 2 Pokemon, I like to imagine the Gyarados that became this volcano was once a Red Gyarados as it is typically featured with Gen 2. But this would not be the only Gyarados to be showcased during World’s Championship on another region.

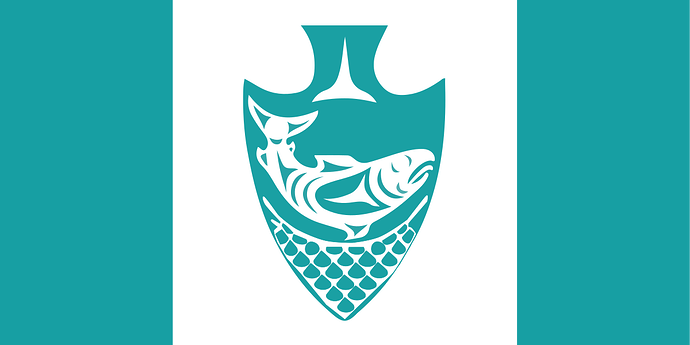

From August 9th - 11th, 2013, Vancouver, Canada hosted Pokemon’s Worlds Championship event at the Vancouver Convention Centre. Pokemon’s theme for the event was an homage to the Indigenous people of Vancouver which holds 3 distinct groups: First Nations, Inuit, and Metis. Vancouver itself is the traditional land of the First Nations of the Musqueam - “People of the River Grass”, the Tsleil-Waututh - “People of the Inlet” or “Children of the Wolf”, and the Squamish who hold the name of their people as the name of their language. These people are few of many of the Coast Salish People.

Stanley Park is likely the location that inspired the totem-pole laden artwork which features Gyarados as one of the totems on this guidebook. The park is a host of different totems created by different artists from several First Nations throughout history. You can read about each one on https://stanleyparkvan.com/ .

The First Nations people’s culture have associations with food, dance, and art, but their cultural roots stem from how they treat and view the land, the earth - with direct ties to the potlatch - an important gifting ceremony - and the use of cedar trees. Totem poles as an example of cedar tree use tell the stories and/or histories of their people.

But how does Gyarados tie in as a representation? It is likely that there is no intended connection, or it could be as simple as using Gyarados as another narrative for the Water and Sky given the importance of both in Indigenous culture. But are there even dragons in their folklore or mythology?

While there are many spirits to represent bodies of water and the sky there are very few dragons known to this Native region. However, there is at least one representation that fits the bill and is probably the most accurate portrayal of Gyarados out of all of the previous mythologies and symbols we’ve explored so far. And it comes from primarily from the Ojibwe people that live around the Great Lakes on the border of the United States and Canada. It’s name? Mishipeshu.

Mishipeshu meaning “The Great Lynx” and also known as the “Underwater Panther” in many other tribes including the Algonquin people, it is known as an entity and symbol of fierce power - responsible for large waves and whirlpools. He is known for claiming victims via drowning and thus appropriately designated as one of the most powerful underworld beings. Described as feline-like with giant horns with a reptillian body and scales like a metal snake (usually copper), he is considered a symbol of good luck when it comes to hunting and fishing and has ties to all water creatures including snakes and serpents. Though associated with a few bodies of water, his primary home is in Lake Superior. A master of the water and caller of storms, his greatest enemy is the legendary Thunderbird. With all the similarities of the horns, ties to bodies of water, death and destruction, scales like metal - one could easily imagine a scenario of the Mishipeshu and the Thunderbird like Gyarados battling Zapdos. One may even think back to the Lake of Rage from Gen 2.

Understanding the deep historical roots and significance of the Coast Salish people cannot be covered by any justifiable means, but I hope folks read up on their culture for it has been a story of resistance and preservation in the face of oppression. Please give them due diligence in learning more about the First Peoples here.

And as we circle back to the Lake of Rage, we come to our final major chapter covering the origins and depictions of Gyarados. But even before all of this began, it’s hard to think that Gyarados could have been anything other than the angry water-dwelling dragon it is today. But what if I were to tell you the first ever origins of Gyarados almost became something else entirely?

What if I were to tell you that Gyarados… Was almost…

A catfish?

December 18th, 2018, Twitter User, @okp108, showcases a picture of an NHK Broadcast in Japan. On the screen are Beta sprites of Pokémon before their final designs approaching the official release. You had Scyther with a more fairy-like design, Lapras without its ears, and a much more Falkor-looking Arcanine from The Never Ending Story.

But then there was Gyarados.

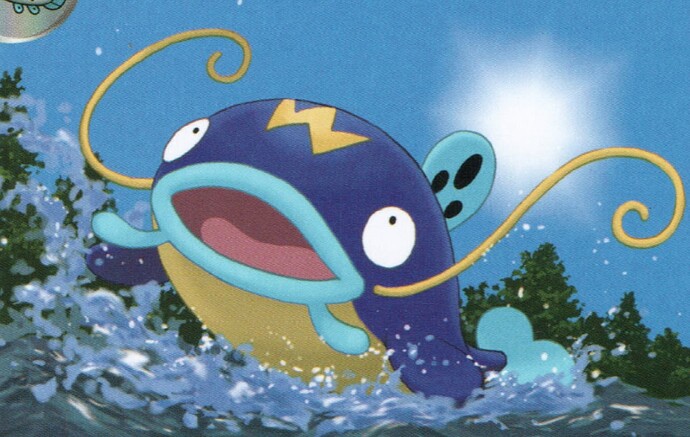

When Beta Gyarados was released to the public, many mentioned its worm-like appearance. Some suggested it looks like the Sandworm from the Dune series, others said it was a leach with weird talons and antennae. However, many would be surprised that the origination of Beta Gyarados’ design wasn’t a worm at all and would be in fact the reason why it has its Pokedex entries of today. One must first see its “claws” more like “fins” and suddenly the barbels on the top of its head give off the impression of a different creature all together - that of a catfish. But what kind of catfish is known for razor sharp teeth and a gaping large mouth?

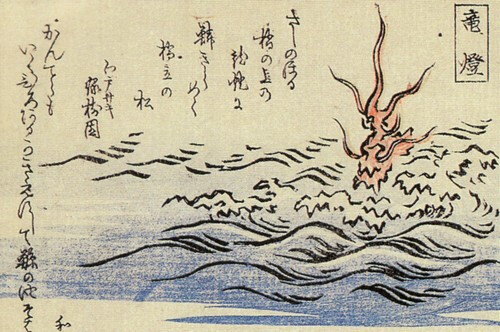

Meet Namazu.

The Giant Catfish deity that causes earthquakes and destroys cities.

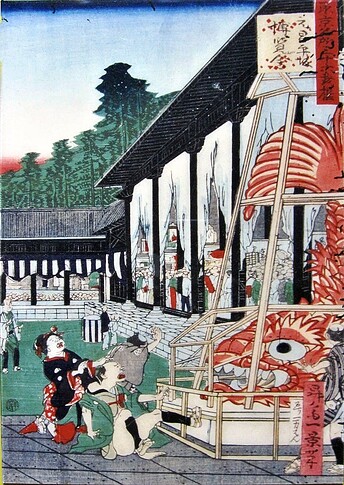

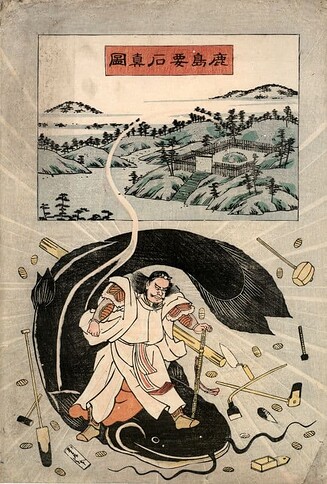

Around 16th Century Japan, earthquakes began around Lake Biwa when catfish were observed to move almost in waves prior to such earthquakes - thus earning their association and becoming the origin of the Namazu myth that would popularize around the 19th century. In 1855, where these prints come from, it was said that Namazu would destroy cities and towns with its earthquakes and thrashing - being responsible even for the Great Ansei Earthquake for the late Edo Period. Many of these also depict the legendary hero and Thunder God, Kashima, who would quell Namazu’s rage and destruction with his sword or what was called the “Foundation Stone”.

Perhaps due to the politics at the time, some even revered the Catfish god as a “world ratification” deity as it was said that it would cause destruction during world conflicts. The latter being exemplified due to the fact that during the Great Ansei Earthquake, nobles and the rich were hoarding wealth but due to the destruction, caused it to be spread amongst the survivors. The earthquake also created jobs for its people and thus began a tradition where people would begin to worship or speak praise of Namazu’s fortune. In illustrations, these fish were depicted with giant mouths of razor sharp teeth and large barbels from the top of their head.

It is here we start to see the similarities of Gyarados as we know today. Even in some Pokédex entries, it is said that the ancient form of Gyarados were known for destroying an entire city - such is the real life case for Edo Period Japan when we consider this origin myth. Consider its other entries from the original first games:

“Huge and vicious, it is capable of destroying entire cities in a rage.” and Crystal’s “It appears whenever there is a world conflict, burning down any place it travels through.” Both Gyarados and Namazu have extremely similar descriptions. Even more-so, Lake Biwa stands as an interesting origin location for both Gyarados and Namazu - being the real-life counterpart to the Lake of Rage in the games. The body of water itself is credited to be the site of earthquakes every few decades and was inspiration for the general shape throughout the two re-designs of Lake of Rage prior to it’s official depiction.

The Lake of Rage may have also held inspiration for Red Gyarados’ color due to the Red Torii Gate whose location lays within the water. With Gyarados Poké Lids designed by Sowsow and Pokémon Go Stations also being centrally located at Lake Biwa in the Kinki Region - Shiga Prefecture.

Given the physical and descriptive similarities with Namazu, it makes sense why Magikarp would evolve into this Pokémon - a fish evolving into a larger fish. If you look closely, you can even see a small eye dot in the Beta Gyarados design. Some may argue that the segmentation of the body is too “worm-like” but remember that Gyarados has natural segmentation and may be related more to a design choice to showcase a creature with “scales” rather than having it be a worm.

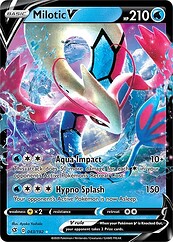

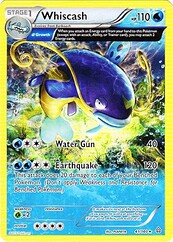

In the end, the design was never used for Gyarados but the descriptions of its origin were. The design for Namazu however would not go to waste as they would eventually rehash it for a Generation 3 Pokémon. In fact, Gyarados could be said to be responsible for the creation of two Pokémon for this Gen. While most might be familiar with the yin-yang nature of Gyarados as an Atrocious Pokémon and Milotic as its beautiful equivalent - sharing similar evolutionary types, stats, and carp-to-serpent qualities. The origins of Beta Gyarados would go on to be rehashed for another Pokemon all together.

Looking at Whiscash, one may only need to imagine it with a longer body and a row of sharp teeth to see the images of Beta Gyarados. Since the myth of Namazu inspired Japan already to use catfish as a symbol for earthquake prevention and creating the myth that catfish could predict earthquakes - the Water/Ground Pokémon was a perfect fit for the redesign. And though it wouldn’t have the same description as Namazu designated for Gyarados’ description, the Ruby Pokédex still provided something similar: “Whiscash is extremely territorial. Just one of these Pokémon will claim a large pond as its exclusive territory. If a foe approaches it, it thrashes about and triggers a massive earthquake.”

And in fact, one need not look any further, for the Japanese name ナマズン literally translates as “Namazun”.

Gyarados continues to make fun appearances and influences multiple Pokémon to this day (with some suggestion that it may have also inspired the look and design of Basculin and Basculegion - another carp-to-dragon-like Pokemon). In consideration to its origins, it was almost named “Skullkraken” for its English release - being based off of Sea Serpents and Monsters, most notably the Kraken before sticking with its original name. In French, it is known as “Léviator” named after the Biblical Leviathan which also has some Ouroboros connections due to “its tail is placed in its mouth”. It’s Chinese name being a bit more literal as 暴鯉龍 “Bàolǐlóng” translates to “Violent Carp Dragon”.

Outside of it’s cultural and symbolic representation, Gyarados continues to influence the world of Pokémon as one of the most popular creatures to feature in its merchandise and promotional material. It is also the Pokemon of many Firsts. Not only was it the first Shiny and first Dragon Pokemon. It was also the first Pokemon to feature as a Mega Evolution in Episode 244, “Yadon’s Comprehension! Satoshi’s Comprehension!” where Misty has a flashback to seeing a Mega Gyarados 10 years before the gimmick was made official and canonized in the TCG as discovering the world of Mega Evolution (though Lucario is canon in the games). It was the First Pokémon to show the Dynamax evolution in the Sword & Shield anime and also one of the first to feature the Terastralize mechanic for Scarlet and Violet.

Why the Pokémon continues to be featured in so many things is up for debate. It could be due to the strong connections to Dragons and main-stream culture even to this day. It might be due to its cool design or the many metaphors that the Magikarp-to-Gyarados evolution portrays. We’ve even see them teaming up with the likes of the Hiroshima Toyo Carp Baseball Team as stand-in Mascots.

The list obviously goes far and wide and though it would be easy to say Gyarados was the primary inspiration for this article (duh), it isn’t the only reason I bring attention to it. Part of the major inspiration for this article was in hopes to inspire Pokémon fans to look deeper into the hidden cultural depictions of some of their favorite Pokémon. TPCI does an incredible job of researching the cultures and inspirations not only for their Pokémon but also the regions and myths they choose to portray. One can start by looking at the cards and graphics featured for Pokémon World Championships or Pokemon Center flyers for easy examples.

What connections can you spot and make?

Circling back to Pokémon Center Singapore as an example, even the simply placed Alolan Exeguttor may serve as a symbolic representation for Singapore’s Supertree Grove featured behind them.

And even things like the under-loved Grimer can be used to inspire cleanliness with Pokémon’s campaign to help keep things tidy:

In truth, Pokémon has the potential to do a lot more good in the world. Who knows what they may choose to do. Perhaps even going so far as to create more environmental support or working alongside different cultures to make positive changes. I would love the idea of Gyarados becoming a symbol for Ocean, Lake, and River protection. A potentially silly idea but I think they have the means to inspire more change as much as they inspire knowledge seeking towards different cultures and mythologies. Whatever the case, I hope this article at least inspires people to look more into hidden roots and see the world at large past the lens of Pokémon. Or at the least have fun with it.

And as for Gyarados. Well. Whose to say when the next cultural depiction of the beloved dragon will be?

After all. 2024 is just barely 2 months away now.

And with it…

Cheers!

- Azul