There are two fundamental terms in collecting. If you don’t understand the difference between them, you’re likely to end up losing money (if you’re someone who buys with the intention to sell in the future) or overpaying for your collections.

I’m talking about the terms “organic collectibility” and “mass-produced scarcity.”

The thing is, seeking “organic collectibility” paired with “absolute rarity” (something that has been produced sparingly and in limited quantities), rather than “absolute rarity” based on “mass-produced scarcity,” is the key to building a collection that holds value over time.

To help you grasp this, let’s first define both concepts and then relate them to Pokemon TCG while examining a few examples.

The Concepts

Organic collectibility arises in objects that, over time, attract collectors but were not created to be collected… but to be used.

This is the case with, for example, early comics, the first editions of Magic The Gathering and Pokémon TCG, or the early video games.

No one in 1993 opened an Alpha Black Lotus (Magic The Gathering) and said, “I’m going to keep this in perfect condition because it will be worth half a million dollars in 25 years.” No one cared about Magic…

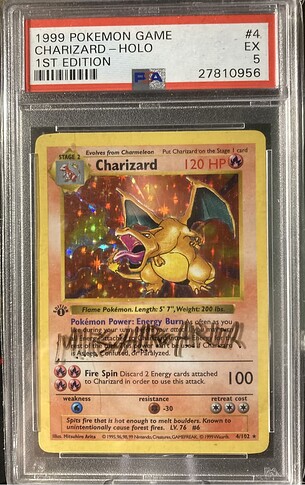

The same happened with Pokemon TCG. When you opened a Charizard, kids like me played with them on the schoolyard without sleeves. They were made for that, to play. And that’s what most of us did.

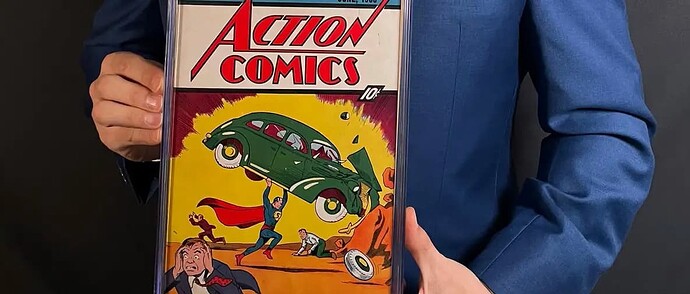

In the 1950s, comics were bought to read and throw away. This is how the natural scarcity that this produces, combined with collectors’ desire that arises over time, the success of certain characters or franchises that no one would have bet on initially, and nostalgia, lead to a comic that cost 10 cents like Action Comics #1 (1938), the first appearance of Superman, selling for 1.5 million dollars in April 2010 (this is not its record).

This is how a PSA 10 Base Set Charizard reaches such astronomical prices, or, to mention something less known among novice collectors, items like a Magikarp University or a Snap Koffing can go for over $50,000. No one who won these last two cards cherished them knowing they could someday have such value… Many were lost from sight and are lost forever.

Just as with Action Comics #1, of which 130,000 were printed but only about 100 remain today…

The desire for an object with organic collectibility naturally arises over something that no one initially paid attention to as a collectible. It’s a characteristic that the market bestows upon something that emerges from collectors’ desires and preferences as time goes on.

On the other hand, we have mass-produced scarcity.

When an object falls into this category, it’s because when it’s produced and put up for sale, people acquire it directly for collecting. From the very beginning, it’s kept in pristine condition, and these products, generally speaking, are never lost or deteriorated.

These types of products are mass-produced but marketed as limited items. Although this limitation is real, it’s so abundant that if you look for it in the market, you’ll always find copies to buy. This translates to the fact that, in reality, they aren’t scarce or rare at all.

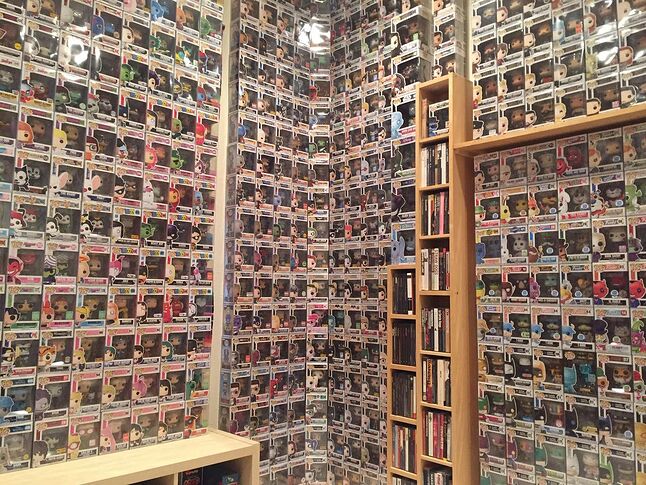

Examples could be Funkos, which no one takes out of the box and keeps in perfect condition. Or modern TCGs that almost no one plays with anymore, but only collect and store in sleeves right after they come out of the pack.

By being mass-produced but in a limited way, a false sense of scarcity is created around them. Their value is subject to significant shifts in demand, as their collectibility hasn’t naturally emerged. This makes them high-risk items for those who speculate or invest in them.

Serialized cards would be mass-produced scarcity taken to the extreme. They are marketing tools executed by companies that, based on consumer greed and the hype these types of items generate, know that booster boxes will sell at lightning speed and at inflated prices.

In sports TCGs, this concept has been exploited for years. But we have a recent and notable example in “The One Ring”.

A desperate attempt by Magic The Gathering to gain traction and attract an audience it has never counted on before: collectors (more on this topic in this other article). It has to be acknowledged that it seems to have worked to some extent, at least in terms of sales and buzz.

And here’s the irrational part…

If you’re not living under a rock, you’ve probably heard that Post Malone bought this card for $2.6 million.

Are we really attributing value to a card that has been printed specifically for this purpose? Are we really giving it more than five times the value of a high-graded Alpha Black Lotus?

We shouldn’t be, but this is the current TCG market. A senseless madness that significantly inflates the coffers of the producing companies, auction houses, and grading firms… at the expense of the average collector’s wallet.

Cards like this will always enjoy a premium in the market due to speculation. And despite not making sense for them to be worth more than the top items with true organic collectibility in the hobby, people will always assign an undeserved added value to them, even though they are pure marketing tools.

But how did we get to this point? When did a hobby, like Pokémon TCG, lose its organic collectibility in its products?

To see an example, we only need to delve into the history of collectibles…

The Transition

There was a time in the early 90s, just after the release of the first Batman movie that stirred the memories and consciousness of the public, when people began to realize that vintage superhero comics were selling for tens of thousands of dollars, and they started looking into that market.

Publishers began relaunching their most popular characters, say Spiderman #1, in 5 or 6 different versions, thinking that collectors would want them all. This resulted in a speculative boom.

People started buying all this mass-printed product, thinking that they could sell it in 30 years to fund an early retirement.

Shortly thereafter, the bubble burst, and people were left with nothing but overproduced comics with no value. This almost led Marvel Comics to bankruptcy, going through the worst period in its history.

The comic industry had a slow recovery. However, despite the crash, vintage comics always remained strong.

Something similar happened with Pokémon in July 2016, with the arrival of Pokémon Go. Many people turned their attention back to a hobby that had been dormant for years and realized that there were valuable cards…

This led people to search their homes and find those binders they kept from their childhood and attracted numerous speculators… to which The Pokémon Company responded with a massive print run of “Evolutions” in November 2016, totaling 1.5 billion cards. Something unprecedented up to that point.

They were forced to ease off the accelerator after a demand drop, only to accelerate again after the 2020 boom. Nowadays, printing such a quantity of cards has become normal, with over 18 billion cards printed in the last two years to meet the current demand.

Reading this, can you see at what point cards transition from having organic collectibility to becoming items of “mass-produced scarcity”?

Pokémon TCG: A Before and After

Pokémon TCG cards before Pokémon Go differ from those that came after, culminating in the transformation following the 2020 boom. Speculation (to which the company responded with appropriate printing) brought various speculative bubbles to the hobby, popping up in different parts of it and continuing to emerge to this day.

Examples range from common cards like Eevee and Pikachu Jungle 1st PSA 10, which reached $1000 (now below $150), to the madness being paid for certain Japanese promos that were printed endlessly and are still yet to correct in price…

It’s true that demand has risen, that the Pokémon franchise is stronger than ever, and there has never been as many people collecting the TCG as there are now.

The problem is that nothing is truly scarce anymore, and almost everything is kept in mint condition (leading also to a loss of conditional rarity). Interest in the game is only from a minority, and cards no longer deteriorate or get lost. Now, cards are made to be collected, and this has its consequences.

Some people seem to treasure cards like Moonbreon from Evolving Skies, hoping that it might pay for their house someday, comparing it to Base Set’s Charizard 1st. Yet, they may not consider that there are close to 100,000 in English and tens of thousands in other languages. Moreover, it’s remarkably easy to get a PSA 10 grade for it, with a Population Report nearly five times higher (7700+) than its count in PSA 9.

What one fails to realize is that a card with such characteristics in terms of print quantity, availability, and condition is a high-risk asset. Even though demand exists for it now and maintains its price, this demand fluctuates constantly.

And when this demand shifts to the “new and shiny”, these assets can suffer greatly as they have the potential to flood the market if necessary.

And if you’re still finding it hard to see this with cards as “recent” as those from Evolving Skies, look at cards like Pikachu VMax Rainbow from Vivid Voltage or Charizard GX from Hidden Fates—once the talk of the town, now forgotten bit by bit (along with their prices).

Could there be exceptions where some of these cards maintain high demand over time? It’s possible. In fact, Moonbreon could be one of them. Despite no longer being the first card that comes to people’s minds, as it did 6 or 7 months ago, it still maintains a relatively stable price (even though you can always find copies for sale). Time will tell how it weathers the test of time…

But just as less than a year ago, everything was about Moonbreon, now it’s Lillies, Ponchos, Marios and Tag Teams… each thing replaces another in terms of attention and demand, and only a few cards with these characteristics stand the test of time.

Examples aside, and with no intention of turning this article into one of speculative theme, I hope the difference between both types of collectibles has become clear.

Which Way Is Pokémon TCG Headed?

I believe that once you enter the phase of manufacturing “mass-produced scarcity,” there’s only one possible path: to move forward.

There’s no way to restore organic collectibility in a hobby that has already transformed, and I’m sure that serialized cards and similar marketing tools will eventually appear.

Regardless, what truly matters is that you understand these concepts so you don’t collect under misconceptions propagated by companies and individuals who profit from it.

If, once you understand these two concepts and collectible characteristics, you choose to collect the latter, that’s perfectly fine. Because that’s what it’s all about – collecting what you love.

I only hope that now, at the very least, you can set realistic economic expectations for them (if that matters to you at all), and, above all, develop a more critical eye for discerning which collectibles truly hold more value (not to be confused with price) than others.

But, above all, you know… Enjoy collecting!

Warm regards,

Cross

P.S. I would love to hear your thoughts on any of this! Or just leave a like so that I can know that you enjoy this type of content (if you did ![]() ).

).